- Introduction

- Immutability and Its Real Impact

- Analyzing with Big O and Benchmarking

- When Immutability Is a Real Problem

- When Immutability Is an Advantage

- Conclusion

- References

Introduction

If you’ve ever heard that “functional programming is slower” or “using immutability costs too much in performance,” you’re not alone. It’s a genuine concern about functional programming paradigms. But is this premise actually true?

In this article, I’ll explore the relationship between immutability (a pillar of functional programming) and code performance, using Big O complexity analysis and real benchmarks. If you’ve already read my article on Functional Thinking, this text is a perfect complement to deepen your understanding of functional programming practices.

Immutability and Its Real Impact

When talking about immutability, there’s a common misunderstanding: “If I can’t change an object, I need to create a complete copy every time I want to make a change.” At first glance, this seems terrible for performance, doesn’t it?

Imagine an array with 1 million elements. If I want to change just one element and need to copy the entire array, that would be disastrous for performance and memory usage. But here’s the secret: copies in functional programming are generally not complete!

The creators of functional languages and libraries are brilliant engineers who perfectly understand this challenge. Therefore, they developed special data structures called persistent data structures (or immutable) that are optimized to work with immutability without severe performance penalties.

Persistent Data Structures

Persistent data structures are designed to preserve previous versions when modified, allowing efficient access to both the old and new versions.

When we modify a node in a persistent tree, we create a new version of the tree that shares most of its structure with the previous version. Only the nodes affected by the change (and their ancestors up to the root) are copied. This is called path copying.

This principle applies to various immutable data structures:

- Persistent linked lists

- Trie-based maps (like those used in Clojure)

- Persistent vectors (like RRB-Trees)

- Hash arrays mapped tries (HAMT)

But what about memory? You might think: “Even with structural sharing, we’re still creating new versions all the time. Won’t we quickly run out of memory?”

This is where another important concept comes in: the garbage collector. When old versions of structures are no longer referenced by your program, the garbage collector automatically removes them from memory. Additionally, modern compilers and runtimes apply additional optimizations that can eliminate unnecessary copies.

Languages like Clojure, Scala, Haskell, and even JavaScript libraries like Immutable.js are notable examples that implement these optimizations.

Analyzing with Big O and Benchmarking

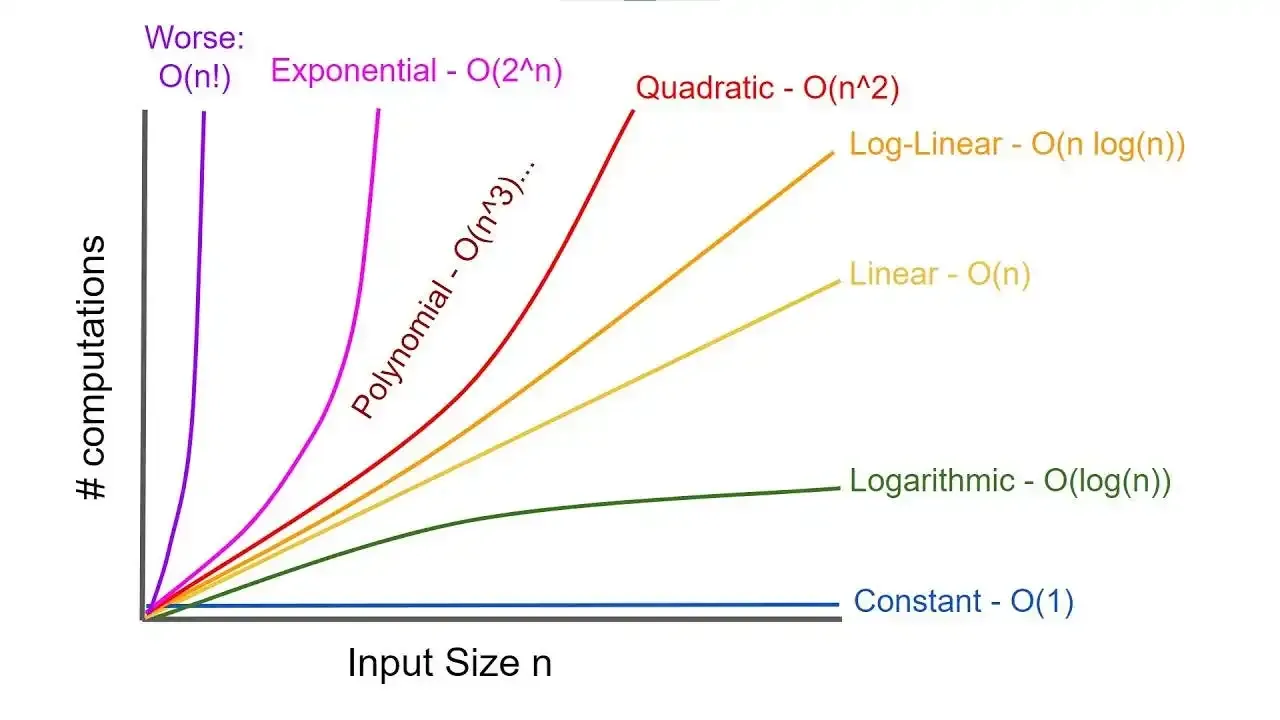

Recommendation: If you’re not familiar with Big O, I recommend this GeeksForGeeks Tutorial on Big O Notation. If you have some familiarity but need a refresher, I recommend this Neetcode cheat sheet.

Comparing Imperative and Functional Approaches

Consider the following task: “Given a list of numbers, I want to filter the even numbers, double them, and then sum everything.”

Let’s compare the imperative and functional approaches in Python:

# Imperative approach

def sum_doubled_evens_imperative(numbers):

total = 0 # O(1)

for n in numbers: # O(n)

if n % 2 == 0: # Filters even numbers in O(1)

total += n * 2 # Doubles and adds to total in O(1)

return total

# Functional approach

def sum_doubled_evens_functional(numbers):

evens = filter(lambda x: x % 2 == 0, numbers) # Filters even numbers in O(n)

doubled = map(lambda x: x * 2, evens) # Doubles the even numbers in O(n)

return sum(doubled) # Sums everything in O(n)

Complexity Analysis

At first glance, the imperative approach seems more efficient because:

- It performs all operations in a single loop

- It has a theoretical O(n) complexity (O(1) + O(n) + O(1) = O(n))

The functional approach:

- Creates intermediate structures for each transformation

- Also has theoretical O(n) complexity with an extra constant for involving multiple loops (O(n) + O(n) + O(n) = O(3n) => O(n))

Comparing Approaches with Empirical Analysis

Let’s consider a more complex example, where we manipulate a collection of users to add a new status:

def add_premium_status_imperative(users):

for user in users:

if user["status"] == "active":

user["premium_status"] = True

else:

user["premium_status"] = False

return users # Returns the same list, modified

# Immutable/functional approach

def add_premium_status_functional(users):

return [

{**user, "premium_status": user["status"] == "active"}

for user in users

] # Returns a new list with new objects

# Let's measure the execution time of both with a larger list

import time

# Generate larger list for testing

users = [

{"id": i, "status": "active" if i % 2 == 0 else "inactive"}

for i in range(1000000) # 1 million users

]

# Test imperative approach

start = time.time()

result_imp = add_premium_status_imperative(users.copy())

time_imp = time.time() - start

# Test functional approach

start = time.time()

result_func = add_premium_status_functional(users)

time_func = time.time() - start

print(f"Imperative time: {time_imp:.6f}s")

print(f"Functional time: {time_func:.6f}s")

print(f"Ratio (func/imp): {time_func/time_imp:.2f}x")

The results show that the immutable approach is approximately 3-4x (on my machine, which doesn’t have a high-end CPU dedicated to intensive processing) slower than the mutable one for this specific case. However, this overhead decreases significantly in optimized code and with more efficient immutable data structure implementations.

What Can We Conclude?

- Yes, there is a difference - The imperative approach is generally faster for simple operations

- The difference is constant - The ratio remains similar as the input grows

- Both scale linearly - Both approaches continue to be O(n)

- The practical impact is questionable - In most use cases, this performance difference is insignificant

In real-world systems, other factors usually have a much greater impact on performance:

- Database access

- Network operations

- UI rendering

- Inefficient algorithms (regardless of paradigm)

Most interestingly, as pointed out in discussions on the topic, the biggest “performance” gain is often not in runtime performance, but in “developer performance.” Immutability makes code significantly easier to understand and debug, which often leads to a faster system in practice because developers have more time to optimize code without being “flooded with bugs.”

For me, the biggest ‘performance’ increase isn’t in runtime performance, but in developer performance. One of the first things I learned working on real-world applications is that mutability is really dangerous and confusing. I’ve lost many hours chasing an execution flow trying to figure out what was causing an obscure bug, when it turned out to be a mutation on the other side of the damn application!

— Developer in the discussion “Does immutability hurt performance in JavaScript?

According to this discussion, immutability allows for very extensive data sharing without real consequences, something that would be risky in a mutable environment.

When Immutability Is a Real Problem

Although the impact of immutability is generally overestimated, there are scenarios where it can represent a real bottleneck:

Numerically Intensive Computing Systems

Let’s imagine a computer graphics scenario, for example, where we need to apply a transformation to an image. How does this work?

In practice, an image in computing is represented as a matrix of pixels (or array), where each pixel is represented by a vector of colors (RGB). To apply a transformation, such as a filter, we need to iterate over each pixel and apply the desired transformation.

It’s certain to imagine that if we have a 1920x1080 pixel image, this means we’ll have 2,073,600 pixels to process. If each pixel is represented by a vector of 3 colors (RGB), we’ll have 6,220,800 values to process.

If every time the image is changed, we have to create a new pixel matrix, this can be extremely costly in terms of performance. That’s why many graphics computing or even Machine Learning libraries like NumPy and Pandas use mutable “in-place” operations to apply transformations, because operations repeated millions of times can be up to 10x slower with immutable structures.

Resource-Constrained Systems

A long time ago, when RAM memory was extremely expensive, mutability was a necessity; in this case, the famous term bit brushing was a common practice. Even today, in systems with limited resources, such as IoT devices, embedded systems, and mobile applications, this practice is still common.

I believe it’s not necessary to elaborate much on why immutability is not generally a good idea for these systems, but think a bit about which programming languages are most used for these systems? What do they all have in common?

Systems with High-Frequency Hot Paths

Hot pathsare code segments that are executed with extreme frequency.

Let’s imagine a company that has a stock broker, where the functionality of Trading (buying and selling stocks in a short period of time) is offered. In this scenario, the system needs to process millions of orders per second, and every millisecond counts. In this case, the allocation of new objects and the pressure on the garbage collector can be problematic.

Here, what actually comes into play is the issue of parallelism in low latency, where the system needs to process multiple orders simultaneously, ensuring data consistency and integrity. Can you imagine such a scenario with immutability?

Game Development and Low-Level Applications

This topic is connected with the topic of Numerically Intensive Computing Systems, but it’s a bit more specific. In games, especially multiplatform ones (that run on different types of hardware), having efficient memory control is extremely important. Have you ever played that game that has average graphics but terrible performance? This could be a sign that the game is not using memory efficiently; that is, there is high reprocessing of objects, unnecessary memory allocation, and among other problems which immutability can and will cause.

When Immutability Is an Advantage

Now that you’ve seen some scenarios where immutability might not be a good choice if you need performance, let’s explore the scenarios where immutability really shines and brings significant benefits.

Concurrency and Distributed Systems

Imagine a system where multiple threads are processing a list of users. If that list is mutable, one thread might be iterating over it while another is modifying it, resulting in Race Conditions, inconsistent behaviors, and even crashes. With immutable data, each thread works with its own Snapshot of the data, completely eliminating this class of problems.

# Problematic scenario with mutable data in a concurrent environment

shared_users = []

# Thread 1

for user in shared_users: # Oops, another thread might modify during iteration!

process_user(user)

# Thread 2

shared_users.append(new_user) # This might break Thread 1's iteration!

# With immutability

# Thread 1

my_copy_users = users.copy() # Or better, using immutable data structures

for user in my_copy_users: # Now we're safe!

process_user(user)

# Thread 2

updated_users = users + [new_user] # New version, without modifying the original

In distributed systems, such as applications based on microservices or distributed databases, immutability becomes practically a requirement. These systems often depend on immutable event logs as a single source of truth, allowing:

- Consistency in distributed systems: each node can work with its own copy of the data without concern for concurrent updates

- Simplified replication: it’s much easier to synchronize immutable events than trying to reconcile mutable states

Tools like Apache Kafka are built with immutability as a fundamental principle, enabling highly distributed, resilient, and scalable systems.

Traceability and Caching

Another benefit is the ability to maintain complete histories and implement caching systems.

Traceability and Time Travel

When your data is immutable, each change creates a new version, naturally creating a history of all changes. This enables:

- Simplified debugging: you can “travel back in time” and inspect exactly how the state of your application evolved

- Auditing: in financial or healthcare applications, where auditing is critical, each change is automatically recorded

Libraries like Redux for React use this concept with their DevTools, which allows developers to literally travel back in time to understand how the application state evolved:

// In a Redux environment

// Each action creates a new immutable state

dispatch({ type: "ADD_ITEM", payload: newItem });

// Later, you can "time travel" to any previous state

// without affecting the action history - this would be impossible with mutable states

Efficient Caching with Referential Equality

Immutability facilitates caching. Since immutable objects never change, checking if an object is the same as another is a simple reference comparison:

// With mutable objects, this is insufficient:

previousCache === newObject // Can be false even if the content is identical, because in JavaScript

// objects with the same values but created separately have different references

// With immutability, this works perfectly:

previousCache === newObject // If false, something definitely changed!

// If true, we guarantee it's exactly the same object (it wasn't modified)

This allows:

- Simplified memoization: functions like

React.memooruseMemoin React can avoid unnecessary recalculations with a simple referential equality check - Change detection: reactive systems can know exactly what has changed and recalculate only what is necessary

Let’s see in React:

// Component using immutability-based memoization

const UserCard = React.memo(({ user }) => {

// This component will only be re-rendered if the 'user' reference changes

return <div>{user.name}</div>

});

// Somewhere in the parent component:

const updatedUser = { ...user, lastAccess: new Date() }; // New object

return <UserCard user={updatedUser} />; // Causes re-rendering

// vs.

user.lastAccess = new Date(); // In-place modification

return <UserCard user={user} />; // Would NOT cause re-rendering!

Conclusion

-

Immutability has a cost, but this cost is often overestimated and generally remains constant (O(1)) or linear (O(n)) thanks to optimized persistent data structures.

-

There are specific cases where mutability is clearly advantageous: intensive numerical computation, systems with limited resources, and high-performance hot paths.

-

There are cases where immutability is decisively superior: concurrency, distributed systems, traceability, and caching.

-

The choice is not binary: many successful systems combine approaches, using immutability in domain and business layers, and allowing controlled mutability where performance is critical.

The most important thing is to understand that paradigms are tools. A good software engineer knows when to embrace immutability for its safety and predictability benefits, and when to relax this constraint to meet specific performance requirements.

Remember: the most elegant algorithm is not useful if it doesn’t meet the system’s performance requirements, but also the fastest code is not useful if it’s full of subtle bugs caused by uncontrolled mutability.

As with many things in software engineering, the answer to “immutability or mutability?” is the classic: “it depends”. Now you have the knowledge to make this decision in an informed way.

References

- Persistent Data Structures - Wikipedia

- Persistent Data Structures and Structural Sharing

- Big O Notation - Neetcode

- Immutability Changes Everything (ACM Queue)

- Why Clojure? - Uncle Bob

- Does immutability hurt performance in JavaScript? - Software Engineering Stack Exchange

I hope you enjoyed this article and that it clarified some of the myths and truths about immutability and performance. If you have any questions or suggestions, leave a comment below or contact me through LinkedIn.